Developing an Annual Training Calendar

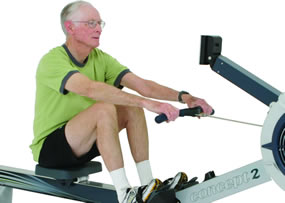

Rowing is a great complement to training for other sports. This section shows you how to develop an annual training calendar and provides workout suggestions that incorporate rowing for general cross-training as well as in training for a specific sport.

- Make a list of the sports you do throughout the year and define the “Active” (or competitive) season(s) for each.

- Define the “Training” season for each sport by backing up three months from the active season. This is when your major training should occur. If you know from experience that you need a longer or shorter training season, adjust accordingly.

- Define the “Groundwork” phase by backing up five months from the training season. This phase focuses on general condition and prep work, giving you a solid base on which to build your focused training.

- Define the rest of the year for each sport as “Recovery.”

Refer to the examples if you need help.

Single Sport, Multiple Season Training Calendar

If you have one sport with several distinct active seasons (for example, a major competition in the spring and another in the fall), your training calendar would look like this:

| Month | Phase | Sport |

|---|---|---|

| January | Training | Running, rowing |

| February | ||

| March | ||

| April | Active | |

| May | Recovery | |

| June | Training | |

| July | ||

| August | ||

| September | Active | |

| October | Recovery | |

| November | Groundwork | |

| December |

Single Sport, Single Season Training Calendar

If you are training for a single sport that has a single active/competitive season that extends from April to June, for example, your training calendar will look as follows:

| Month | Phase | Activity |

|---|---|---|

| January | Training | Triathlon, golf, paddling |

| February | ||

| March | ||

| April | Active | |

| May | ||

| June | ||

| July | Recovery | |

| August | Groundwork | |

| September | ||

| October | ||

| November | ||

| December |

Multiple Sport, Multiple Season Training Calendar

Following is an example of a multi-sport training calendar. This example includes a regatta season in the fall, Nordic ski races through the winter, and a marathon and shorter runs during late spring and summer. The active phases are spread out; the training, groundwork, and recovery phases overlap to become cross-training for each other, with rowing acting as the common thread.

| Month | Rowing Phase | Running Phase | Nordic Skiing Phase |

|---|---|---|---|

| January | Recovery | Groundwork | Active |

| February | Groundwork | Training | |

| March | |||

| April | Recovery | ||

| May | Active | Groundwork | |

| June | |||

| July | Training | ||

| August | Recovery | ||

| September | Groundwork | ||

| October | Active | Training | |

| November | Recovery | ||

| December |

Training for Each Phase

- Groundwork—Emphasize longer, steadier work. The goal is to develop a good base of general cardio conditioning and adjust your muscles to the specific motions of your sport. Include plenty of stretching, flexibility, and strengthening exercises.

- Training—Tailor your workouts for the distance and intensity of your upcoming events. You will need to train a bit at your race pace to develop a sense of pace for your competition. Include shorter, harder work to increase your intensity level, and longer, easier work to improve endurance.

- Active—Keep sharp and rested during this phase, and recover between events. Increase your workload if your events are fewer and further apart.

- Recovery—This phase is about variety, fun and whatever pace feels right. Incorporate lots of stretching. Keep in tune with your sport by doing a few steady state workouts at a comfortable pace.

Sample Workouts

Before trying these workouts, please read our liability disclaimer.

Try the following workouts to train for your sport:

- 40 minute steady state row (or 10,000m) (Groundwork and Training).

- 40 minutes of one minute hard, one minute easy (Groundwork and Training).

- 1-2-3-4-3-2-1 minute pyramid with 30 seconds off between pieces (Training and Active).

- Three minutes at 18 spm (strokes per minute), two minutes at 24 spm, one minute at 28 spm. Continue cycle for 30–60 minutes (Training and Active).

Workout frequency: 2–4 times per week during the recovery phase; 1–2 times per week during the Active phase.

Duration: 30–60 minutes. Shorter for intense, speed workouts; longer for steady state aerobic workouts.

Type and intensity: Vary this between steady state, anaerobic threshold work, intense intervals and racing pieces.

The Force Curve graphically represents how you apply force (or power) during the rowing stroke, indicating how your total force varies as you use your legs, back and arms during the drive:

The Force Curve graphically represents how you apply force (or power) during the rowing stroke, indicating how your total force varies as you use your legs, back and arms during the drive:

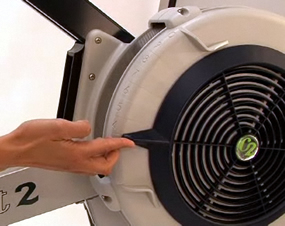

The damper is the lever on the side of the flywheel housing, or fan cage, that controls how much air flows into the cage. The fan cages on our later indoor rowers (Model C and later), are numbered so you can set the damper lever to a particular value from 1–10, indicating how much air is drawn into the cage on each stroke:

The damper is the lever on the side of the flywheel housing, or fan cage, that controls how much air flows into the cage. The fan cages on our later indoor rowers (Model C and later), are numbered so you can set the damper lever to a particular value from 1–10, indicating how much air is drawn into the cage on each stroke: It’s no surprise that hands can take quite a beating from rowing. Blisters generally develop first, followed by calluses. The good news is that calluses offer protection: once your hands are callused, they should bother you less than when you first started. Even with calluses, be careful about suddenly increasing the duration of your rows—especially in hot or wet conditions, which accelerate blister formation. The key is to increase your rowing time gradually. Also, avoid letting your calluses get too thick. Clip or sand the top layer of dead skin when necessary.

It’s no surprise that hands can take quite a beating from rowing. Blisters generally develop first, followed by calluses. The good news is that calluses offer protection: once your hands are callused, they should bother you less than when you first started. Even with calluses, be careful about suddenly increasing the duration of your rows—especially in hot or wet conditions, which accelerate blister formation. The key is to increase your rowing time gradually. Also, avoid letting your calluses get too thick. Clip or sand the top layer of dead skin when necessary. Of the three points of contact, the feet may have it the easiest—no gripping, no body weight, no impact. But, for ultimate comfort, it is important to find the right combination of socks and shoes. Choose good socks and shoes that aren’t too wide at the heel or have a heel with too much rise. (Wide heels can affect how well a shoe fits in the heel cup on the indoor rower, and shoes that rise too high may irritate your Achilles tendon at the finish of the stroke.)

Of the three points of contact, the feet may have it the easiest—no gripping, no body weight, no impact. But, for ultimate comfort, it is important to find the right combination of socks and shoes. Choose good socks and shoes that aren’t too wide at the heel or have a heel with too much rise. (Wide heels can affect how well a shoe fits in the heel cup on the indoor rower, and shoes that rise too high may irritate your Achilles tendon at the finish of the stroke.) The butt has a lot to do during rowing. It supports your body weight, serves as a pivot point, participates in the rowing stroke itself, and gets sat on the whole time. If your butt is not happy while you’re rowing, chances are the rest of you isn’t happy either.

The butt has a lot to do during rowing. It supports your body weight, serves as a pivot point, participates in the rowing stroke itself, and gets sat on the whole time. If your butt is not happy while you’re rowing, chances are the rest of you isn’t happy either.